There's only one copy of this handwritten dictionary for an imaginary language — and it's in St. Louis

"The Versalian Dictionary" is a 2,000-page, hand-bound prescription for world peace.

Libraries are known for the word “Shh,” and they’re known for long reading tables filled with bearded men in parkas and hoodies, who arrive in the morning and spend hours slowly reading newspapers from A1 to the comics. A good number of these men show up for the heating and cooling vents, not the news of the day.

Throughout the late 1940s and early 1950s, a small, rumpled guy with sparse gray hair and a silvery five o’clock shadow arrived at the St. Louis Public Library every afternoon and joined the readers of newspapers at a big library table. He pulled dictionaries in every language from the shelves, sat for hours studying them, and took notes in cheap, blue-lined notebooks.

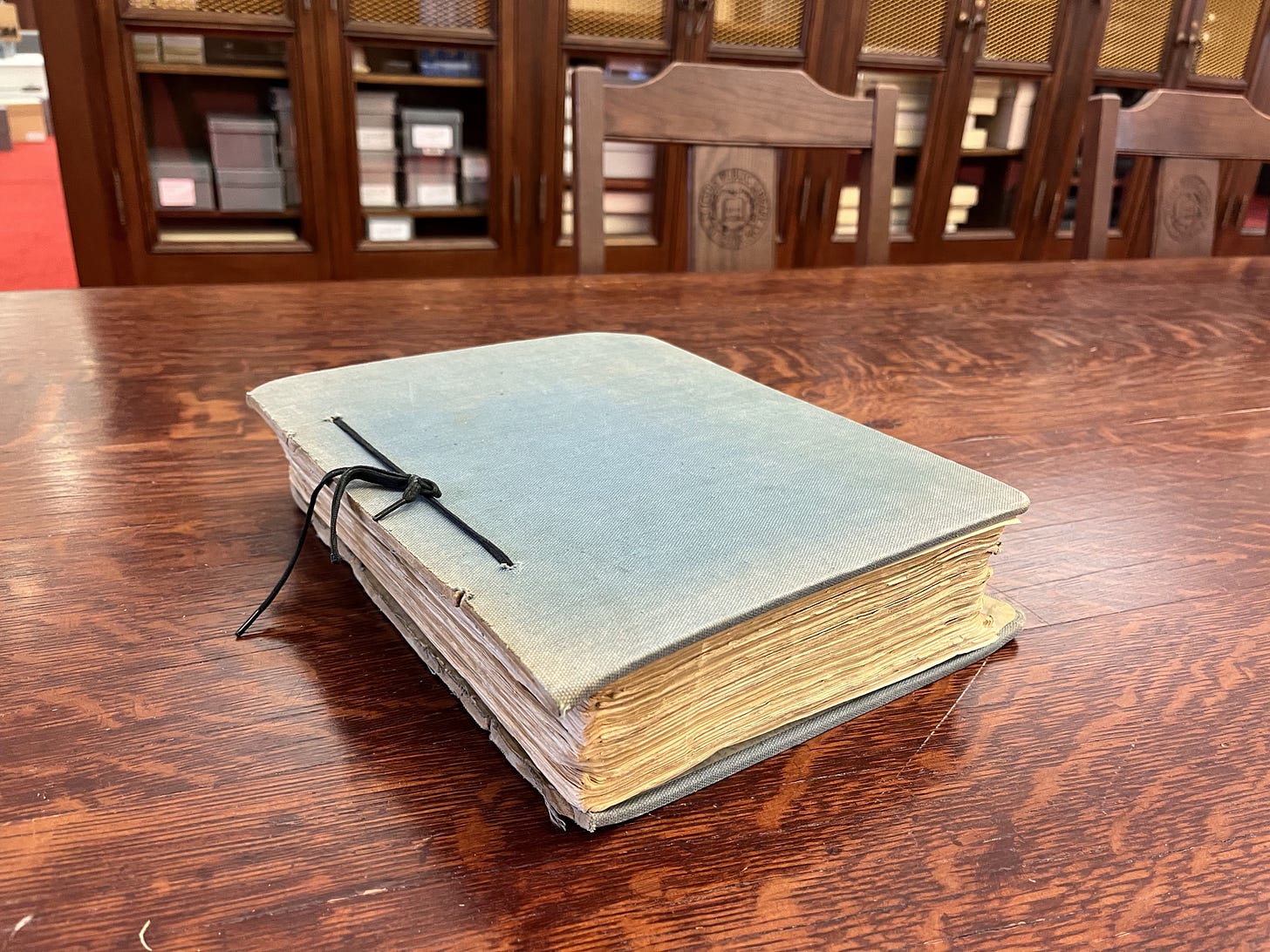

Then, sometime around 1957, he presented a bewildered librarian with a gift: a 2,000-page book, handwritten in pencil: The Versalian Dictionary, by Peter M. Kosta. He asked that it be added to the stacks.

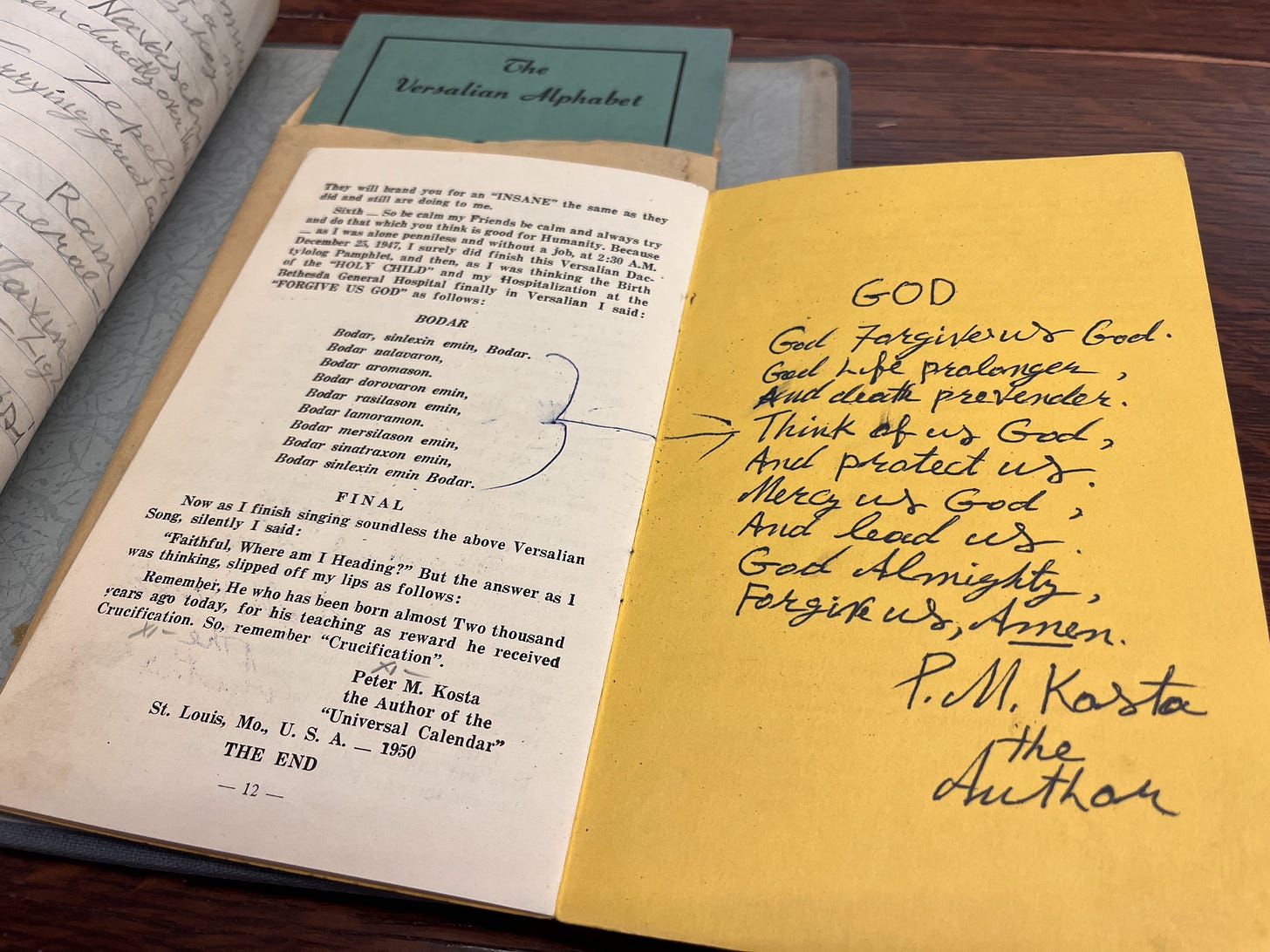

Bound between two blue covers tied together with a black shoelace, it included a sleeve inside the back cover holding a set of pamphlets, self-published in 1947: “The Versalian Dictionary,” “The Versalian Dactylog,” and“The Versalian and English Arithmolog.”

A few years later, in 1962, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch got wind of this curious book, and wondered if it’d make a good color story. A reporter hotfooted it down to the library, took a look, and tracked Kosta down at the St. Nicholas Hostel on South Broadway, where they pestered the clerk about Kosta’s whereabouts.

The Versalian Dictionary, the Post discovered, was a skeleton key to Kosta’s invented language, a universal dialect with a stripped-down alphabet that’s superior to Esperanto (which Kosta explains in the preface).

“He believes that the number of languages in the world make a ‘Tower of Babel’ of communication,” said the Post. “He set about formulating a language that all men could use directly with their fellow men.”

Peter Mihal Kosta was then in his late 60s, living on Social Security and suffering from high blood pressure. An Albanian immigrant, he’d dropped out of school in the 4th grade. In the 1940 Census, he’s listed as married, renting a house in Soulard and working as a shoe cutter; 10 years later, around the time he was feverishly working on The Versalian Dictionary, he was a lodger in a shabby hotel on South Broadway, working 70 hours a week as a bartender in a tavern. He listed his marital status as “never married.”

The Post described Kosta as “short, stocky and balding,” unshaven, often wearing an open shirt and baggy trousers.

“He takes his meals at a sandwich shop just around the corner from his room in the hotel,” it wrote. “Often, he walks during the morning hours, or sits on benches in the park behind the library or next to the Pierce Building on Fourth and Chestnut Streets. Surrounded by summer sunlight and clucking pigeons, it is perhaps here he dreams of a world untied by Versalia. In his own words, his goal is ‘Panselviesin Anelina so Namo nasio Lenisan Versalia’ (Universial peace for every nation through Versalia).”

The Universal Calendar

Kosta shows up in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat even earlier, though — for a different, but still very universal, reason.

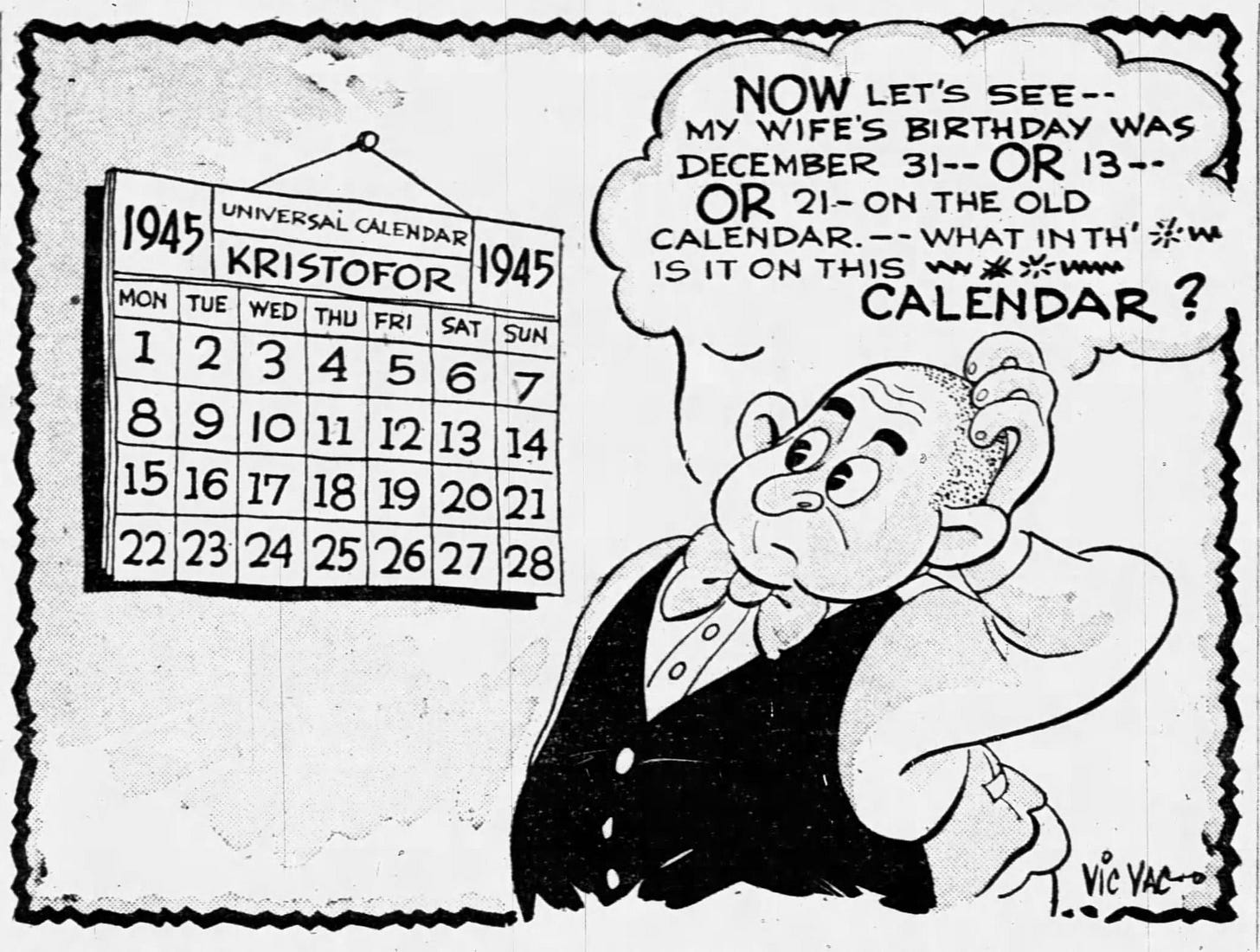

In 1944, in an article on American “calendar reformers,” the Globe interviewed Kosta as the only St. Louisian in the bunch; naturally, he proposed the world adopt a universal calendar.

“We gave it special study, then interviewed its author, Peter M. Kosta, at 2628A Allen avenue,” reporter Margaret Maunder wrote. “The 13 months of the Kosta or ‘Universal’ calendar read as follows: January, February, March, April, May, June, July, August, FOLTON, EDISON, BELL, MARK and KRISTOFOR, the last five being named for the inventors of the steamboat, incandescent lamp, telephone, telegraph and for Christ, respectively. Each. month has four weeks, 28 days, with every week and every month beginning on Monday. Of course, Folton isn't spelled exactly the way Robert Fulton spelled his name — but it's close.”

Kosta argued the logic of his calendar: “Be honest with yourself. If 60 seconds make a minute, if 60 seconds make an hour, if 24 hours make a day, if seven days make a week, then 28 days make a month.”

After undertaking “a mathematical tabulation the likes of which are rarely found outside Einstein's waste basket,” Maunder concluded that Kosta’s calendar would result in the opposite of world peace.

At first, she said, it would be easy if all Mondays were the 1st, all Tuesdays were the 2nd, and all Fridays were 13ths. “But when you start translating birthdays and anniversaries from the Gregorian to the Universal calendar, you are inviting paranoia in by the front door,” she said. They’d all shift, and you’d end up confusing your kid’s birthday with your wedding anniversary. The only static holiday would be Christmas, on 25 KRISTOFOR.

When she confronted him about the wonky math — specifically what would happen to the extra day at the end of the year, and the leap year day every fourth year — he told her, “I say to you in short and plain American, skip them both just like that!”

The Universal Alphabet

The Versalian Alphabet has four vowels and 14 consonants, 18 letters in all: ABEDKLMNOSRPVFTXIZ. Kosta spent more than 12 years creating Versalian, including a numbers scale that allows you to say or write long numbers in a shorter way, and a Versalian sign language. “Aristotle was wrong, he said, in declaring that without speech there can be no thought,” the Post wrote. “Kosta can ‘say’ this with his fingers in Versalian.”

The dictonary’s preface includes explanations on pronunciation, syllabics, capitalization, accents, and punctuation. Kosta also smattered in some philosophical musings here and there.

The most compelling part of the text is the dictionary itself, which reads like a long poem. Each lexical entry is a surprise; it includes an English-to-Versalian translation of each word, followed by definitions in English.

Kosta taught himself English by reading dictionaries, which is why he had such a great love for them. That wasn’t just Albanian-to-English dictionaries, but dictionaries in French, German and Spanish.

Kosta apologized to the Post for his “poor command” of English. But as a non-native speaker, and as scrutinzer of many dictionaries, his syntax, and his point of view, are wonderfully and peculiarly his own:

A: or is the First letter of the English Alphabet. Also for the Versalian Alphabet but the sound in the Versalian Sounds as in Father.

Caterpillar — Rayamala. The hairy wormlike of lightwingy insects.

Census — Ziraxm. Official enumeration of the inhabitants.

Chick — Polapol. The young baby hen child chick.

Daffy — Antim. Unsound mind.

Drum — Rondo. The instrument beaten with sticks.

Drumstick — Salesam. The Fowl's leg from the knee to the heel.

Eyebrow — Rasterlim. The hairy arch above the eye.

Fairy — Imelansin. An imaginary being of graceful.

Flirt — Zizimi. Make love from mere amusement.

Horse Laugh — Xanelsam. A course noisy laugh.

Movement — Astenasm. The mechanism of the Watch.

Movement — Milnels. The evacuation of the bowels.

Neighing — Enlklim. The cry of a horse.

Owl — Didon. The night bird.

Owl — Nadidon. Person who keeps late hours.

Photograph — Zanistaskirm. Picture taking by lightwriting.

Radiance — Anelsim. The Brilliant Brightness.

Snow — Sno. Frozen of vapor.

Sweatshop — Lizmem. Place where employees are overworked.

Tricksy — Trikrim. Given to tricks.

Vaccinate — Simimash. To innoculate with vaccine against smallpox.

Zebra — Zibra. A wild animal of Africa with black and white stripes.

Zebra — Zibrelim. Black butterfly with yellow stripes.

“Life Without Ambition is Death”

“Long before I have founded and formed the Versalian Alphabet, I have been talking as an insane man, saying this few words to myself: ‘Nations will live in Peace and harmony as Brothers under the Sun only when an International Language can be founded and understood by all Nations,’” Kosta wrote in his pamphlet on Versulian. “But for a long time I also mistrusted my own ideas till the Great National Leaders of America, England and Russia met from place to place in which, they have been discoursing through interpereters the War and Peace of the World for years to come.”

Then, on July 30, 1946, Kosta grew so ill he was admitted to the hospital. “As I was almost breathless from fever and asthma, I smashed the orange which I was trying to eat,” he wrote. “‘Life without ambition is death. Now before you die, you have to find and form the alphabet for the new language.’ Yes, in the first day of August, 1946, as I was sick in the Bethesda General Hospital, I founded and formed the first Versalian alphabet.”

While convalescing at Bethesda, he wrote prayers in Versalian, translated poems from Latin to Versalian, and wrote “Bodar,” (“God”) a song written entirely in his new language.

He was released from Bethesda while still sick, and ended up living in the park between the library and Soldier’s Memorial for three nights, because his room had been let; in the following months, he was in and out of the hospital three times.

That experience motivated him to the extreme, and he wrote his Arithmalog from a hospital bed, “because, as we all know, ‘Death takes no holiday.’”

Gripped with a fervid desire to spread the gospel of Versalian, he flipped a coin on Friday, December 13 to decide what newspaper to contact.

“The St. Louis Globe-Democrat won,” Kosta wrote. “Now as I was down but not out, I have lost no time. But, I have made know to the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, but, as I receive no answer, finally I said.

Father;

According to my knowledge,

Right-or-wrong,

I did my part.

So help me--God.”

Maybe Kosta flipped another coin and decided to reach out to the Post. Maybe the reporter found out about Versalian one night while having drinks with a librarian. Either way, Kosta finally got his press coverage.

When the Post lost track of him in 1962, Kosta was traveling from library to library, handwriting “a converation book of Versalia,” until a severe attack of high blood pressure landed him in the hospital again.

“His friends at the hotel do not know to which hospital he was taken, and calls to major charitable hospitals in the city failed to find him,” the paper wrote. “The hotel clerk reported that a relative appeared to take him a away one afternoon last week. But is likely that in the future another manuscript written in pencil will turn up at the muncipal library sigend by Peter Kosta, the Author.”

That never happened. Perhaps Kosta was just too sick to continue, though he lived for several more years; he died in 1967, at the age of 72. His obit lists surviors as: a sister, Athina Spiro; two nephews, Chris and Ted; a niece, Helen. It’s likely that it was Athina who arrived at St. Nicholas to gather him up.

His funeral was held at St. Michaels Orthodox Russian Church; he’s buried at Saint Matthew Cemetery on Bates Street in South St. Louis.

There is no photo of his headstone on Find-a-Grave. No one has left a comment or left digital flowers. But Kosta’s dream lives on in a scruffy, lovingly written dictionary in the rare books room at the St. Louis Public Library. Right or wrong, Kosta did his part. And he did it for humanity:

The date when God created the World and made Man, only God knows. But to us it is unknown.

Further unknown to us is who the First Person was that discovered the First Alphabet, through which he formed the first words for the children of his time and ours, through which words they has been and still call on parents, Mom and Pop.

But of course that which we all know, not only the characters, but also the sound and pronunciation of the Alphabet has been changed according ot the sound and pronunciation of the different languages. But after all don't forget, the originator and all the Reformers of the Alphabet are and will be as they were always topsy for me. For surely they were only people and Citizens, of the one and only World.

Another amazing article!

This fascinating article is about a little known frequenter of the Saint Louis Library during the late ‘40s and ‘50s, Peter M. Kosta. As the article informs us, he came to believe that if there were a universal language there would be world peace. He set about creating such a language and named it Versalian, creating the alphabet and a dictionary for this very purpose.

Whether he was aware of it or not, this goal thrust him into the predominant philosophical issue of his time in Anglo-American philosophy: what is the relationship of words and sentences with the world? If what the words say is true, then what the words mean has to be real, actual. How?

A groundbreaking thinker in this area was Ludwig Wittgenstein, an Austrian Professor of Philosophy at Cambridge University. His Philosophical Investigations, published posthumously in 1953, is still a seminal work in the philosophy of language.

Among other questions Wittgenstein raises is whether a Private Language is possible? I like to imagine Kosta studying Wittgenstein at the Saint Louis Library. And I wonder what Wittgenstein would have made of Kosta’s achievement.