The St. Louis artist who invented the Doomsday Clock

Martyl Schweig Langsdorf was painting until her death at 96. But she's most famous for a simple magazine cover.

Seven years before she designed the art piece that would make her famous, Martyl Schweig shocked the Postmaster General of Russell, Kansas by showing up to paint the mural inside the main post office. And by being a 22-year-old woman.

“A daughter of artists — her father is Martin Schweig, West End photographer, her mother Aimee Schweig, a painter — it was expected that she would be a good artist, but further than that, Martyl has won honor on top of honor, and with paintings, not of flowers and pretty landscapes but of city slums and subjects of social signficance, and such man-sized jobs as the brawny-men-in-wheat-fields theme of the recently completed mural,” wrote the St. Louis Post-Distpatch, in its story on her mural commission.

Schweig agreed it was unusual for women to paint murals. “There are only five or six other woman mural painters in the United States, and I’m the youngest,” she said. “Mural painting does have its unglamorous side, of course. There's a lot of saw and hammer and nail work in making the framework for the canvas. The actual painting took only two weeks, but there were so many prelimanaries that the correspondence between Washington and me is high.”

She said she wanted to hear comments from the people in the town, because she knew she'd gotten everything exactly right. "I know just what they’ll be looking for," she said. “They'll look to see if the right pitchfork is used, and if the stacks are right and the grain the right length and what tobacco the farmers are smoking.” She'd spent a lot of time in Ste. Genvieve — where her mother co-founded an arts colony — and she knew her stuff. Plus, she said, “I’ve had farmers check them for me.”

She said she intended to buck the sexism of the time and become a well-known artist, despite her gender. "Women have been held back in art because men don't like to make concessions and it's all a man-made world, after all," she said. “One funny thing — people never think a woman did my painting. They expect women to do little anemic things.”

Of course, this being 1940, the writer had to comment on Schweig’s cute, curly bangs, and ask if she happened to be engaged. No, she said, but grinned and said, “I always have said that marriage and a career do mix.”

Eventually, Martyl dropped the Schweig, and just went by Martyl — but not because she stayed single.

A few years after this photo was taken, she married another St. Louis native, Alexander Langsdorf. They stayed married for life. And she kept up her briliant art career the entire time.

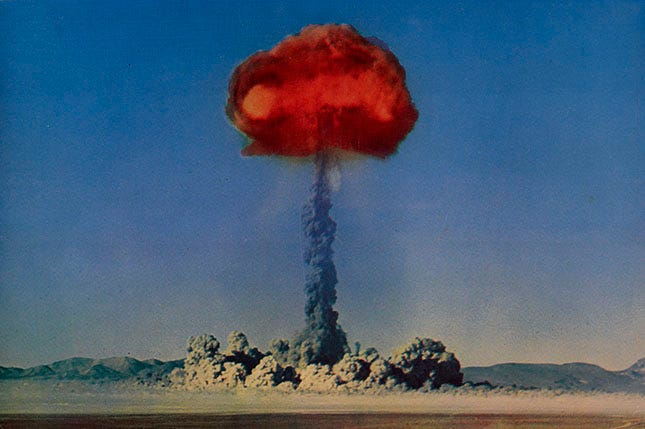

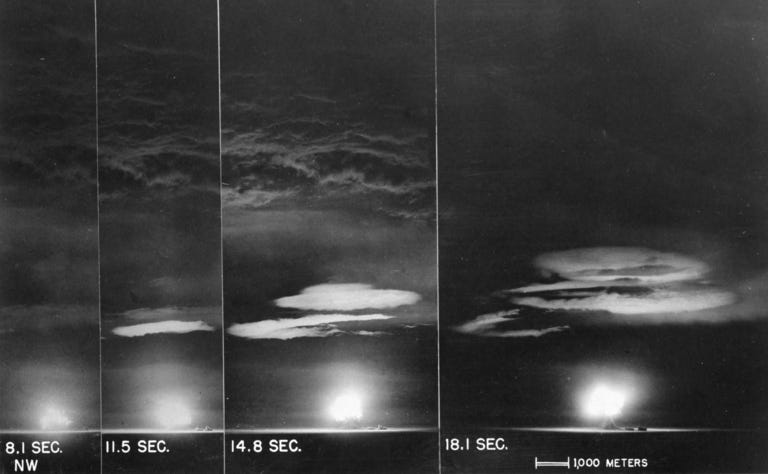

When they met, Langsdorf taught physics at Wash. U., and helped develop a cyclotron for splitting atomic particles. It was supposed to be used for medical research, but Langsdorf’s skill as a nuclear physicist soon landed him a spot on the crew of the Manhattan Project. When he and Martyl were newlyweds, they moved to Chicago, where Alexander worked under Enrico Fermi. He was part of the team that created the world’s first nuclear chain reaction; he became known as the “plutonium pioneer,” because he isolated a wee mote of that element — enough to fuel the Trinity nuclear test.

As the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists noted in its obituary for Martyl, she found herself adjacent to conversations among these scientists, many of whom “had grave reservations about using the weapon on civilians. So in 1945, as they realized the terrifying significance of the United States’ plan to drop these bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, they began organizing meetings to debate and discuss their invention. Their arguments spilled out beyond labs and classrooms into dining rooms in private homes and onto platforms in public halls. Sometimes heatedly, and always passionately, they spoke of the role and responsibility of the scientific community in creating the most dangerous technology on Earth.”

Her husband, along with 70-odd other scientists, signed the Szilard Petition, hoping to prevent the Truman administration from dropping nuclear weapons on Japan.

“He thought it was unbelievably inhumane to drop it on an open city and kill so many civilians,” Martyl told the New York Times after her husband’s death. During a teaching post in Japan in the 1970s, the couple found themselves on a train that passed near the Hiroshima shrine. All the other passengers disembarked to pay their respects. But Alexander, Martyl said, “just sat there with tears in his eyes.”

Though the petition failed to stop the bombing of Japan, The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, which is still tracking the threat of nuclear war, became a cultural force and helped launch the antinuclear movement. Langsdorf, as a member of the Atomic Scientists of Chicago, helped spearhead the Bulletin; the first issues were mimeographed newsletters, but when it was redesigned as a glossy magazine in 1947, Martyl stepped in to design the cover, and eventually became the magazine’s art director.

She first conceived a design using the letter “U,” for Uranium, but then decided that the image needed to reflect the emotional weight of the threat of nuclear war. She began with a simple image of the Earth, overlaying a clock face over it, with its hands set to seven minutes to midnight. She admitted that the time was arbitrary — that her take was aesthetic, and was meant to create a sense of urgency. “It seemed the right time on the page,” she said. “It suited my eye.”

First called the Atomic Clock, it’s now know as The Doomsday Clock. Seventy-five years later, it’s based not just on nuclear threats, but climate change. It’s reset every January, and two months ago, it inched the hands to 90 seconds to midight —“the closest to global catastrophe it has ever been.”

A scan of the news just in the past week confirms why. The war in Ukraine has officials worried about the safety of this nuclear plant; Putin is rattling sabres at the world, and so is North Korea; 10 drums of nuclear material are missing in Libya; a nuclear power plant in Minnesota has repeatedly leaked radioactive water dangerously close to the Mississippi River.

“I’m leaving a world in terrible shape and terrible in all ways that I’ve tried to help make better during my years,” Daniel Ellsberg told the New York Times last week, after announcing a ternimal cancer diagnosis. “President Biden is right when he says that this is the most dangerous time, with respect to nuclear war, since the Cuban missile crisis. That’s not the world I hoped to see in 2023. And that’s where it is.”

When Martyl died in March of 2013, her clock hands stood at five minutes to midnight. Since she first designed it, those hands have jumped backwards and forwards, with the most hopeful year being 1991, when it clicked backwards to 17 minutes. The clock also inspired other artists, including Iron Maiden and Allan Moore.

Martyl said she was amused about being “the clock lady,” and while she didn’t downplay the impact of her design, continued to focus on her paintings, which are in collections all over the world, including in the Smithsonian. You can go to Russell, Kansas and still see Martyl’s post office mural, as well as the one she painted two years later for St. Genevieve’s post office that depicts La Guillonée, the centuries-old French New Year's Eve ritual that’s still observed in the town. She returned in 2000 to take a look at it and do some repairs. “After all those years, people came back to watch me work,” she remembered. “All the young people that watched it being painted years ago, now were old.”

As her St. Louis Public Radio obit noted, Martyl didn’t consider herself old at 70. When she died 10 days after turning 96, she was in the midst of planning a solo show, Works on Paper and Mylar 1967-2012, for the Printworks Gallery in Chicago, which opened as scheduled.

Her brother Martin Schweig — an artist in his own right — noted this was all typical of his ambitious, focused sister, who had her first gallery show at 11, sold her first painting to George Gershwin, and beat Tennessee Williams in a Wash. U. playwriting competition.

“She had prepared for it,” he said, “and was completely ready.”

Next Week: A deeper dive into Martyl’s paintings through the lens of the Nettlesome Artists of Group 15, which included Belle Cramer and Martyl Langsdorf’s mother, Aimee Schweig. In the meantime, check out Martyl’s daughter, Suzanne, reflecting on her parents’ antinuclear work.

What a fascinating woman! Maybe the secret to a long life is having ongoing projects. I had to check out what La Guillonee is, too. Fascinating and beautifully written. ♥️