New Orleans versus the heavy hand of Robert Moses

The Letters Read series dives into the archives to look at what "the master builder" had to say about NOLA.

On the first Sunday of JazzFest, thousands of people were at the Fairgrounds, getting sunburns and listening to Gary Clark, Jr., Jill Scott and Kenny Loggins (who’s out for the last time, he says. We’ll see!).

And about two dozen folk, including me and Thomas, were at The Orange Couch for the first post-pandemic, in-person event with Letters Read.

It’s a really nifty concept. It’s an “ongoing series in which local performers interpret letters and written documents about culturally vital individuals from various times and Louisiana communities.” In other words, it presents history as theater by letting the dead speak for themselves, bringing “audiences into intimate moments usually experienced while reading a personal letter from one whom one knows.”

An ongoing labor of love by stationer Nancy Sharon Collins (with support from Antenna :: New Orleans), its now in its seventh season; it’s looked at “Lady Louisiana artists,” letters sourced form the streets of New Orleans, and letters of regret. (You can listen to some of those productions here.)

Collins’ latest project looks at how “master builder” Robert Moses impacted the City of New Orleans using his “writings, letters, and other contemporaneous articles” that she accessed through the New Orleans Public Library, the Williams Research Center and The New York Public Library, among other archives.

As you can see from this search return, the jury is still out when it comes to Moses’s legacy:

Looking at those search returns, one of the most remarkable parts of Collins’ informal reading of her script-in-progress was the way just reading Moses’ own words shrank the guy back to human scale — not a prophet, but not Darth Vader, either. She chose him, she said, because she went looking for a connection between New York and New Orleans, and found his 1945 report, Arterial Plan of New Orleans, commissioned by the state of Louisiana “to evaluate, and recommend, remedies for common, mid-20th-century problems such as traffic congestion.”

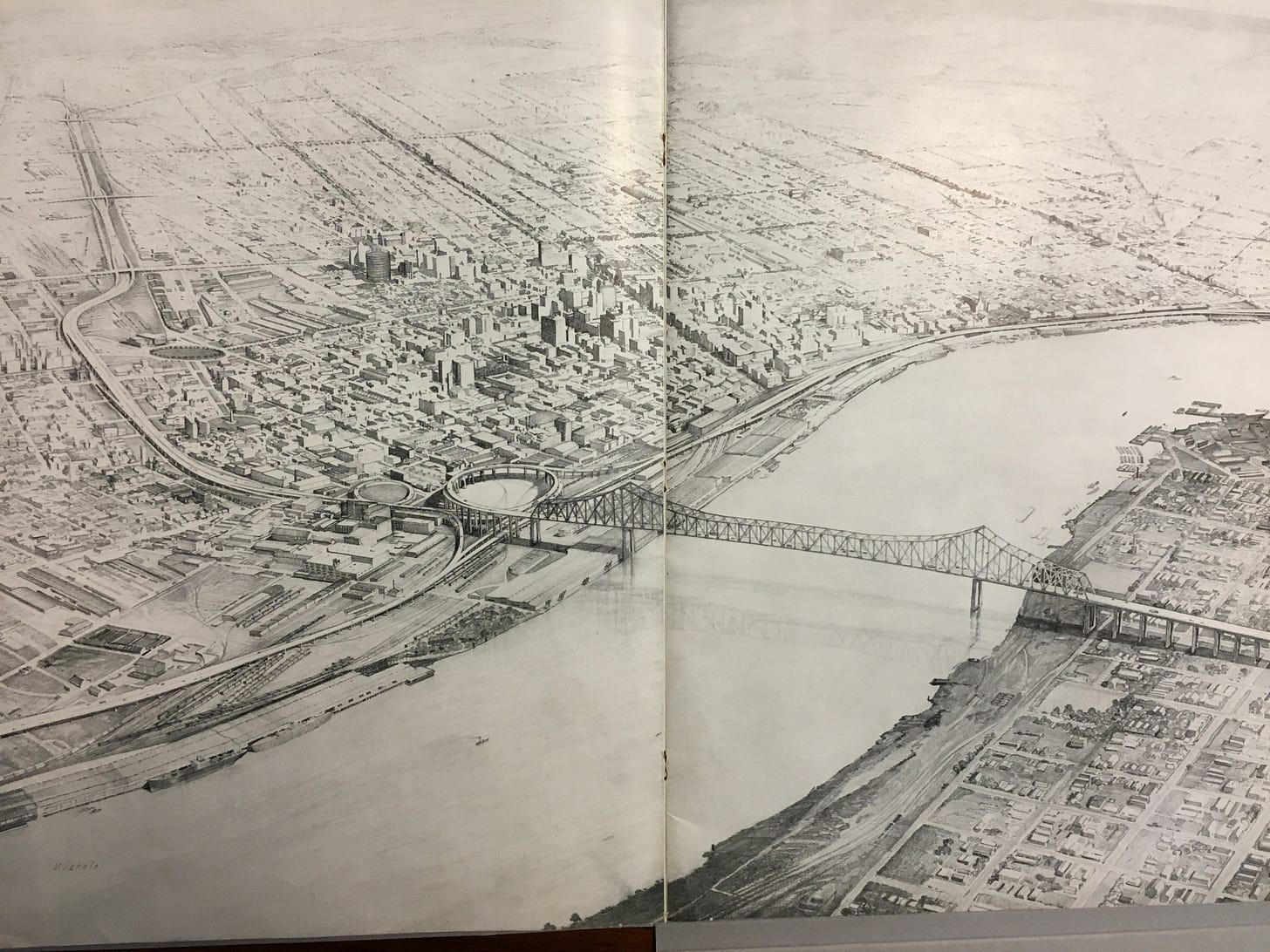

Sunday’s event looked at Moses’ proposed Riverfront Expressway, which never happened; had it come to pass, it would have separated “the historic Vieux Carré and the Pontalba Plaza from the Mississippi riverfront entirely. Literally throwing the historic residential neighborhood, a significant tourist destination, into the shadows.”

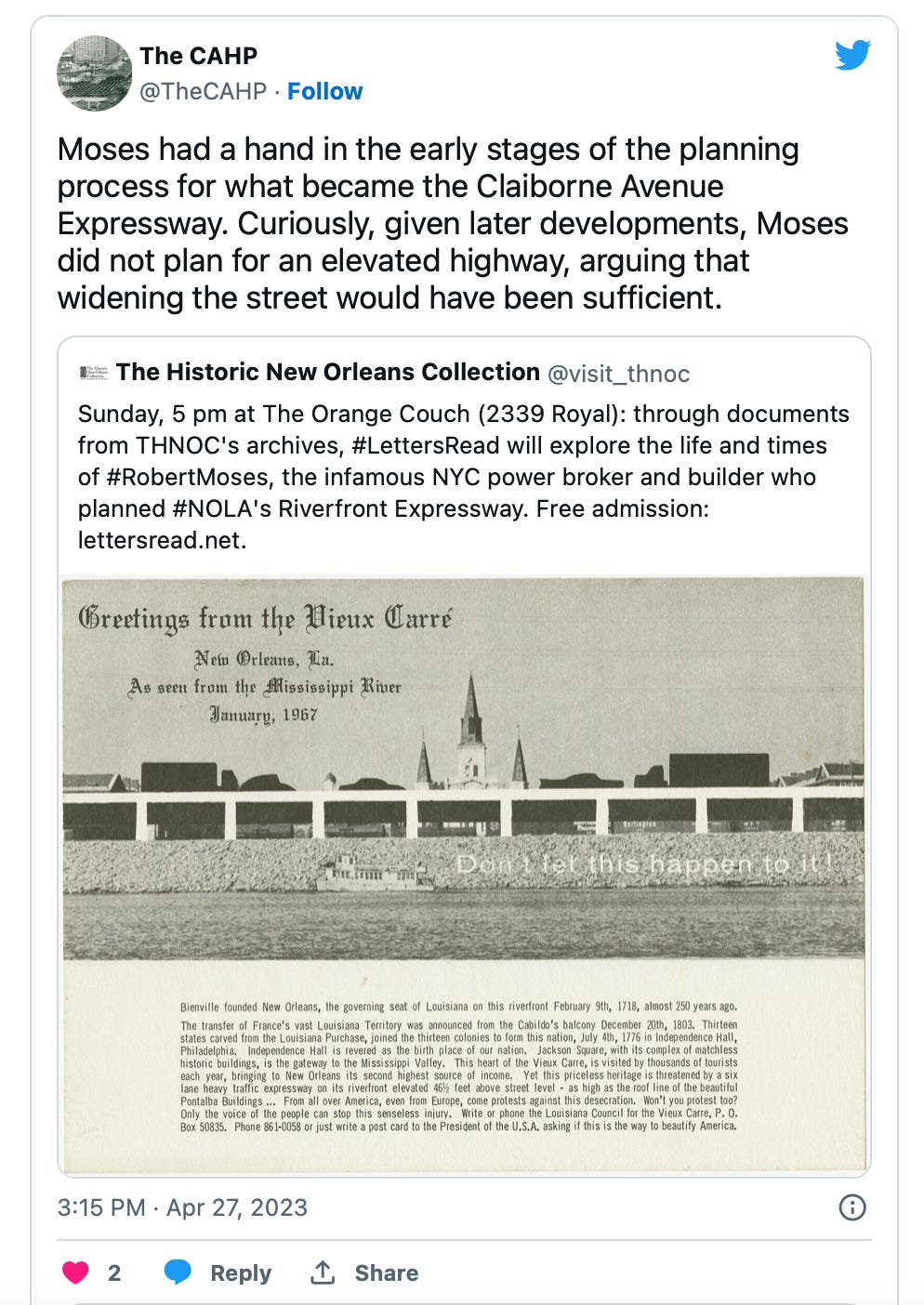

Thanks to pushback from local preservationists, the Riverfront Expressway never made it out of the rendering stage. But Arterial Plan of New Orleans looked at the city as a whole — it “outlined the modernization of all Crescent City transportation.” Collins pointed out that the city would have suffered a terrible historical, architectural and cultural losses had Louisiana decided to take Moses’s advice on the expressway — but it also ignored his advice about Claiborne Avenue. Rather than widening Claiborne — which was what Moses recommended — the city demolished a vibrant swath of Tremé to build the I-10 Interstate Bridge, AKA “the Monster,” clearing out hundreds of century oak trees and Black-owned businesses.

The Claiborne Avenue History Project

As Smithsonian noted in 2021, “when the Federal Highway Act of 1956 earmarked billions of dollars for interstates across the country, New Orleans officials advanced two projects proposed by planning official Robert Moses. One targeted the French Quarter, then a mostly white neighborhood that was already famous as a historic part of the city. The other focused on Claiborne Avenue. While well-connected local boosters managed to block the French Quarter plan, many in the Tremé neighborhood weren’t even aware of the plan for Claiborne, as no public hearing process existed yet, and officials didn’t bother consulting with local residents.”

If you want to get a deep, close look at what New Orleans lost when I-10 was constructed, check out The Claiborne Avenue History Project, a multimedia archive co-created by educator Dr. Raynard Sanders and filmmaker Katherine Cecil. CAHP was featured in Global Highways, online exhibit at Georgetown University, which put Claiborne in the context of other neighborhoods around the world that were destroyed to make way for infrastructure. The text and photos draw a rich, vivid picture of what was lost in the name of efficient traffic flow:

When construction of the interstate began in earnest, residents immediately felt the loss of their established ways of life. Businesses closed, gathering places changed character, and the atmosphere shifted from that of a shady boulevard to a hot, concrete streetscape. Jazz historian and photographer William "Bill" Russell documented some of the landmarks that began to disappear as construction of the highway proceeded. The intersection of Claiborne and St. Bernard Avenues had once included a traffic circle with a landscaped green space at the center. Russell's photograph of Louisiana Undertaking highlights the changing character of life and death as a result of the interstate. Neighborhood landmarks, such as the home of founding-era jazz clarinetist Alphonse Picou, suffered in the aftermath. Though Picou, pictured behind his bar, had died in 1961, his home continued to serve as a place of reverence in the neighborhood.

And continuing on the theme of music, it continues to describe the cultural loss that occurred when the neighborhood was cleared:

The number of music venues on Claiborne Avenue speaks to its status as an artery for the Tremé and Seventh Ward neighborhoods. Many interviewees emphasized that the side streets radiating from the main avenue contained as many clubs and bars as Claiborne itself. Drummer Benny Jones, a founder of the Tremé Brass Band, gave us a tour of “fifty barrooms or better” that he said stood on the side streets showed how they all led back to Claiborne Avenue. Jones guided us through a typical parade route. Many mentioned the Nightcap Lounge, the jazz club Terro’s, the Desert Sands, the Giant, Prout’s Alhambra, the Honey Hush Club, Big Mary’s, and the Off-Beat Club. Each club, as Moore ruefully noted, “ain't there no more.”

Robert Moses isn’t totally off the hook, though CAHP agrees he’s off the hook for Claiborne:

Moses said that cities are traffic. I find that to be a very bleak point of view, and a flawed one, too. Cities are people. They are coffee shops and grocery stores and bike racks. They are families barbecuing in picnic pavilions. They are flowery weeds popping up on the side of sidewalks, and the bees that land on them. They are porches and the conversations that happen there. They are porches and the concerts that happen there. They are cars, too, and the people inside them — who are usually experiencing some of the worst moments of their day.

When Letters Read unveils its full production, and we can hear Robert Moses himself talking about New Orleans in 1945, it’ll be a way of rethinking the city — including the idea of demolishing I-10. Though a lot of people say it’ll never happen, as Big Easy reported in April, there’s an increasing push to make it happen. Architect Amy Stelly of Claiborne Avenue Alliance Design Studio is currently working with the city to measure air quality and noise levels in order to build the case for demolition.

“The City can’t have it both ways,” she told Big Easy. “They can’t say they’re all about equity on the one hand, and then — with the other hand — take this data which is going to show dangerous levels of air quality and noise pollution and do nothing about it. Do they care about this neighborhood or not? It’s finally time to decide.”

Thanks to Fred Rhoads, owner of Orange Couch, for tipping us off to Letters Read and Collins’ event, and for explaining both the Expressway and Claiborne Avenue to us a few days before the talk.

In Seattle, an ugly viaduct highway that separated downtown Seattle from Elliot Bay was torn down—a reverse act of engineering that corrected a long ago mistake. But the pandemic and various other forces have prevented the city from creating a new identity for that open space. It used to be parking lots shadowed by the viaduct and now it's parking lots open to the air.