Looking for Carlotta Bonnecaze, the first woman Mardi Gras float designer

Plus: what is Historiola!? And what is it fixing to do?

A post on Carlotta Bonnecaze (because it’s Twelfth Night).

Nothing makes me mentally itchier than mysterious dead people. Carlotta Bonnecaze is currently in my top 10 driving-me-crazy history puzzles.

She’s credited as being the first woman, and the first Creole, to design Mardi Gras floats and costumes, primarily for Proteus, the second-oldest Mardi Gras krewe.

On December 30, my partner and I moved from St. Louis to NOLA. (By the by, you can find him here on Substack as well, at Thomas Crone’s Memory Hall and the very new, new, new Newbie Orleans.)

We closed on a house in Musicians’ Village on December 30. Which was also my last day as the food reporter for the Salt Lake Tribune. That was a head-spinner, for sure.

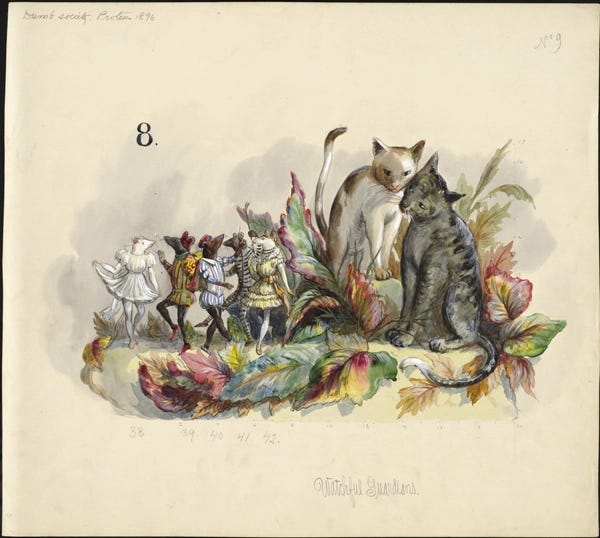

That day, I took down a 19th-century image of Salt Lake’s griddy street system and replaced it with an image I’d found via the Public Domain Review: Bonnecaze’s 1896 Mardi Gras float design for the theme “Dumb Society,” featuring a bunch of cold-blooded creatures — terrapins, parrots, alligators — dressed in party frocks and dancing under a bower made from giant hummingbirds.

Like pretty much everyone seeing her work for the first time, I immediately plugged her name into a search engine and read and re-read the phrase “the mysterious Carlotta Bonnecaze,” because … no one really knows anything about her. She wasn’t even publicly credited for her work until 1922 — not a shocker for the time. But Jennie Wilde, another woman artist active in the late 19th and early 20th century, at least has a sliver of a biography, including her art school training.

It takes a float designer to know a float designer

The expert on Bonnecaze is NOLA native, historian and float-builder Henri Schindler, who literally wrote the book on parades and costumes — Mardi Gras New Orleans — in 1997. In his 2002 book, Mardi Gras Treasures: Costume Designs of the Golden Age, he dedicates a chapter to Bonnecaze, noting that he’s spent 20 years chasing her ghost.

Between 1885 and 1897, he writes, Bonnecaze painted 1,000 plates for costumes alone, and that’s not taking into account her float designs —she’s credited with the biggest cache of surviving Golden Age Carnival art.

During her 12-year run, she explored Indian, Chinese and Greek and Scandinavian mythology, as well as some wild takes on the natural world. All of it, as Schindler writes, “stamped with her unique romantic strangeness and zany good humor.”

Her first designs were themed around “Myths and Worships of the Chinese,” including a series of floats “aglow with opulently jeweled walls and vaulted ceilings of precious metals, gardens of bejeweled palm trees and golden vines, and other secense of heavenly splendor”; her last, 1897, interpreted Ariosto’s long poem, “Orlando Furioso.”

The confusion demographic algebra of “the mysterious Carlotta Bonnecaze”

A skill I accidentally acquired while working in journalism (something I explain below) is spelunking through archives, both online and physical.

Any genealogist, including half-hearted amateurs, will say the only way to get truly accurate birth-death dates is to go creeping through a cemetery and make a headstone rubbing. The Internet, even Find-a-Grave, is not a cemetery.

I love physical archives, not to mention graveyards, but in the age of digitization (not to mention COVID-19), it’s sometimes easier to find what you’re looking for online. It also helps that the primary site of genealogist info exchange no longer AOL message boards, but professional sites like FamilySearch, where people often back up their claims with now-affordable DNA tests.

So, to the web I went, itchy and curious. I dug through the web, through Newspapers.com, FamilySearch, and GenealogyBank. Bonnecaze’s name is unusual, it’s hard to believe there’d be eight or nine, or even two.

“The name — Carla Bonnecaze — could hardly be more exotic,” Schindler writes. “Worldy and faintly decadent, eccentric, and theatrical, it is a name Lafcadio Hearn might have created for the heroine of a New Orleans tale of spendidly overgrown ruins and Creole ghosts.”

Find-a-Grave lists one Carlotta Marie Bennecaze. Her birth date is 1887, which would mean that she began executing sophisticated designs for the Krewe of Proteus two years before her birth. Most sources give her father’s name as Alexis or Alexander Bonnecaze, but the records don’t record any descendants for that person; Carlotta is listed as the daughter of Alexis’ brother, Leonce Hippolyte Bonnecaze.

Just to triagulate some info for the often-inaccurate Find-a-Grave, I pulled up online census records, and found one Carlotta Bonnecaze in New Orleans, born “22 mars 1887 (22 Mar 1887),” to Leonce and Odile.

A dive into newspapers.com shows a Carlotta Bonnecaze working as an art teacher in May of 1911:

Two years later, in September of 1913, the paper reported that Bonnecaze recieved her certificate as a French teacher. In 1924, she’s listed as a delegate at an education conference in Shreveport. That’s two years after the Louisana State Museum’s archives discovered her name attached to her Carnival designs. This Carlotta — which I can’t prove is the Carlotta — doesn’t show up in the newspaper records as an artist. The next big blip on the radar is her death in March of 1930 at the age of 42, just a few weeks shy of her 43rd birthday.

The Dumb Society

Even though all the numbers are wacky, I’m going to agree with Schindler: that “the work that should remain, for now, attributed to Bonnecaze.” And that the best way to know her is through her work, even if the mystery never gets solved.

Schindler’s take is that her finest designs were for 1896’s “Dumb Society” (they certainly flipped my wig!) where she played with gently satirical scenes of animals doing human things.

“What set ‘Dumb Society’ apart, what placed it among Carnival’s greatest works was the sly charm and perfectly pitched humor of Bonnecaze's watercolors,” he notes. “Each of the pageant's 18 scenes was set amid the paper-mache decors of nature and featured varous members of the animal kingdom, all clothed in human costumes and performing human activities…Lion presided at the table of ‘A Royal Banquet’ before a group of elegantly clad large cats ... white mice primped and pranced in organdy pinafores beneath the steady gazes of ‘Watchful guardians,’ papier-mache cats standing 18 feet high.”

“More than a century later, the Bonnecaze paintings for ‘Dumb Society’ remain a wry, one-of-a-kind masterpiece,” he continued. “The cast of this Mardi Gras menagerie appears as lively and winning today as they were on the night they performed their inspired pantomimes.”

And those pantomimes really do continue, at the International House Hotel. In the two weeks leading up to Mardi Gras, they hang Bonnecaze’s “Dumb Society” watercolors on the walls and hold teas at Loa, the hotel bar. They’re inspired by her painting “Five O’Clock Tea,” where a lady elephant on an oversized red chaise sits down for a fancy tea with a couple of monkeys and an assortment of ruminants. In the painting, “she pokes fun at at affected custom. The painting is also the inspiration behind Loa's most enchanted tea party — a must-see late afternoon fête served theatrically by costumed creatures in mid-to-late February, from 5 to 6 p.m. each day, complete with make-believe animal noses and tasty rum-tea punch.”

Historiola?

This is a history newsletter, kinda. I started writing history stuff at St. Louis Magazine waaaaay back in 2005 when I joined the staff as culture editor. For years, I wrote a weird back-page column based on archival photos. After I left the mag, I began working with St. Louis’ Informal History collective, both the podcast and the ‘zine. (Now that I’m freelancing, I hope to contribute more essays to IH. You can follow them on Facebook here.)

Those gigs taught me that I love dowsing archives and finding lost stories, or new takes on stories that’ve been told too many times. Sometimes, it feels like topics throw themselves in my path in an almost eerie way. Other times I feel like I’m shrimp trawling through newspapers.com for a few days before anything interesitng pops up. Either way, I’ve always tried to connect the big with the little, putting one person’s day-to-day life into the context of larger historical forces, to cast the mundane in more mythic terms.

Good ol’ Wikipedia defines Historiola as “..a modern term for a kind of incantation incorporating a short mythic story that provides the paradigm for the desired magical action.” The word dates to Greco-Roman times, and Mesopotamia before that.

PS, a hat tip to Carl Nordblum, author of Historiola: The History of Narrative Charms. He writes about a very old, very specific, very Scandinavian tradition (my Black Sea German ancestors practiced something similar). This is not that! But it’ll defnitely tilt more toward mythos than logos.

A coda

My aim is to write about NOLA past and present with humility, being honest about how much I don’t know and don’t understand yet. Hopefully I’ll bring something new to the table.

We’ll be back and forth between STL and NOLA, and so topic-wise this newsletter will be meandering up and down the Mississippi as well, sometimes drawing connections between cities. Just like the river is a whole system, so are regions, and St. Louis and New Orleans are points along a constellation of cities with linked histories and destinies.

But tonight, it’s all NOLA. And we’re going to the first parade of carnival season, organized by the Krewe de Jeanne d’Arc. And that’s what I’ll be talking about next week.

You don't know how happy it makes me to be able to follow your funky, kooky, word wizardry here. Can't wait to see you in a couple of weeks for beignets. I'll be the one in the black t-shirt.

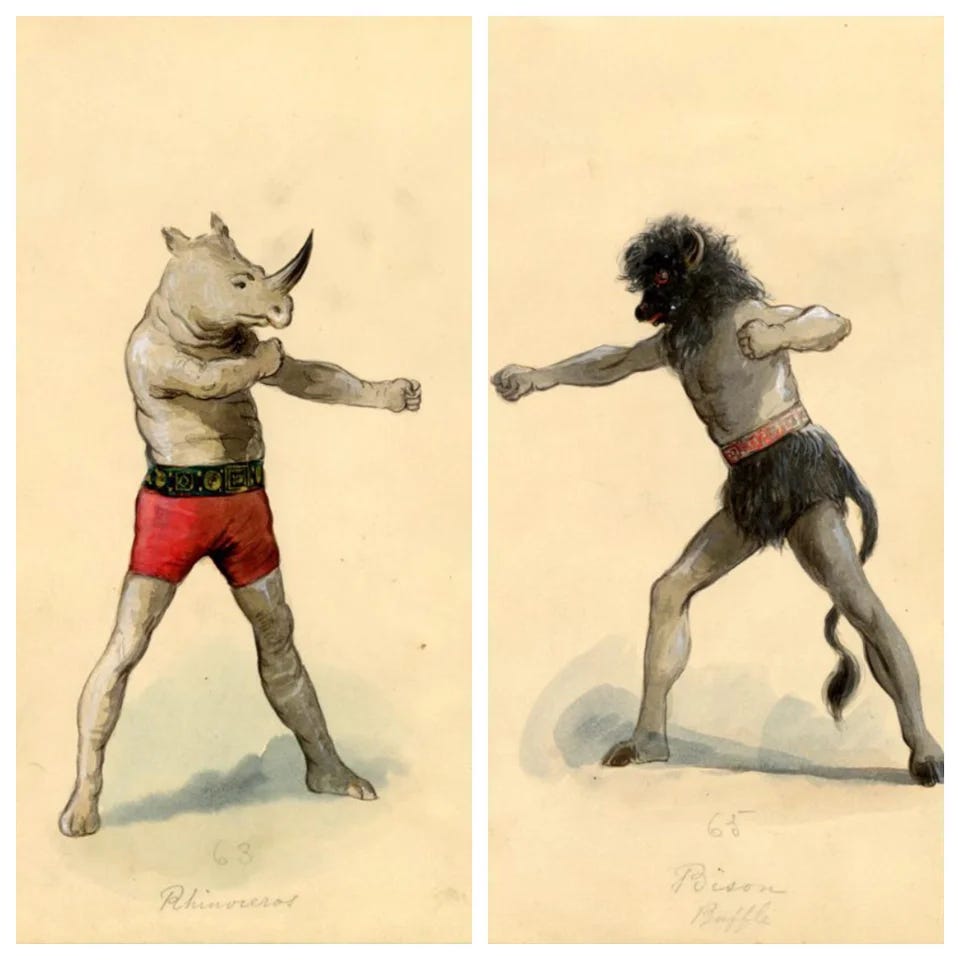

Those sparring critters are disturbingly svelte after the bluster and dominance their heads would connote!