"Ladies and gentlemen, one of the great moral forces of the world has just walked in the door"

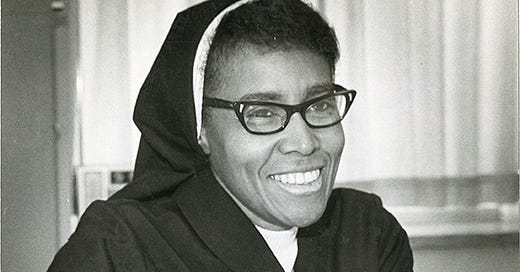

Remembering Sister Antona Ebo

If you read Monday’s New York Times, you saw this incredible piece about the Kung Fu Nuns. Thank you, Jim E., for sending me the link, as well as sending me the obit for Mormon feminist Linda King Newell. (There’s a post brewing with the latter, for sure.) If you haven’t read either of these stories, both are well worth your time.

This weekend, fierce nuns were already on my mind. Newbie Orleans and I went to Mass on Saturday afternoon at St. Francis Xavier Seelos in Bywater, where they hold services in both English and Spanish. There’s a lovely image of Our Lady of Guadelupe on the left-hand side of the altar. Which reminded me of Sister Mary Antona Ebo.

In 2007, my editor at St. Louis Magazine assigned me to write an oral history piece about Black St. Louisans who’d experienced segregation firsthand. After some research, it was clear I needed to talk to Sister Ebo. On March 10, 1965, she was the only Black sister to travel with a group of six nuns from the Sisters of St. Joseph to march for voting rights in Selma with Dr. Martin Luther King, three days after Bloody Sunday. It was not the safest journey for her to undertake. She always said she had no desire to be a martyr, “But God called my bluff.” She felt the call, and she answered.

When she took my call, she answered, but wasn’t super happy about it. “I don’t want to talk to you,” Sister Ebo told me. She was undergoing chemo, and weary of telling the same stories over and over again. “But you called on the Feast Day of Our Lady of Guadalupe.” Her saint. “And that means I have to talk to you.”

We met at her house in U. City, and clocked two six-hour conversations over two days. She was cranky, warm, funny, generous and stern. And a wonderful storyteller, too.

For those who don’t know Sister Ebo: This piece in America: The Jesuit Review tells the story of her life before and after Selma; the PBS documentary Sisters of Selma: Bearing Witness to Change follows her world-changing trip to march for voting rights, including her entrance at Brown A.M.E. Chapel before the protest, where Andrew Young — a New Orleans native, by the by! — introduced her by saying, “Ladies and gentleman, one of the great moral forces of the world has just walked in the door.” (The two didn’t see each other again until March 10, 2014, when they both attended the Urban League of Metropolitan St. Louis’s annual dinner, 49 years to the day they met.)

When Sister Ebo marched in Selma, she was already breaking down barriers. She was 40 years old, and just been named the director of medical records at St. Mary’s — the first Black supervisor in the hospital’s history. In 1946, when she joined the Sisters of St. Mary in St. Louis, she was one of the order’s first three first Black postulants, along with Sister Hilda Brickus and Sister Therese Townsend. And 21 years after that, she became the first Black woman to head up a Catholic hospital when she was named executive director of St. Clare's in Baraboo, Wisconsin. The following year, she helped organize the National Black Sisters’ Conference, which is still going strong.

Sister Ebo died at the age of 93 on November 11, 2017, nearly 10 years to the day after our conversations. She hoped by telling her story again, it would echo out and keep the changes coming. As it turns out, she told her stories many more times after we spoke, and pushed for change right up to the end, including in Ferguson, where she joined young people in the streets to protest. She also visited Ferguson’s Our Lady of Guadelupe Church on March 10, 2015, exactly 50 years after the march on Selma, to lead a prayer for peace.

Because my piece was a collage of voices, I was only able to use a short snippet of my conversation with her. I’ve always wanted to post larger excerpts from her interview. The Saturday encounter with Our Lady of Guadelupe, plus the story about the Kung Fu nuns, seemed like a nudge to do just that. Here are some outtakes from those two marathon interviews, 16 years ago.

On Sisters of Selma

If you follow that documentary, it [the Voting Rights Act] got passed a couple of weeks after the sisters went down, and the whole country got disturbed. Fifty-fifty they were opposed or for it, but within about two weeks’ time, Johnson had signed that Equal Rights Law. And we shall overcome… well, we haven’t 40 years later.

On losing her father to the segregated hospital system

Yesterday, I debated in my own mind, now I should I tell her about this incident? But then I thought, well, maybe there are other things to talk about. Because I can spin my web for a thousand years, and the little fly is still trying to get out of the web!

Like I told you yesterday, I came down from Bloomington to St. Louis, working through the hospital, not being able to find a Catholic school of nursing in my own home town of Bloomington. The land of Lincoln, and yet I had to do some powerful praying that God would open something up for me. The only avenue I could find was St. Mary’s, and over the door, it said, “for the colored.”

It was an old, inadequate hospital that had been closed for whites when they built the big St. Mary’s. Well, it was considered big then — now it’s just a little cracker-box, with everything else built around it. But that became for white folks. And the bottom line of that was, for me, in 1952, I had been in the order six years, or I went into the formation program, I hadn’t had first vows, I had temporary vows, and my father was brought down from Bloomington to St. Louis in an ambulance, because the sisters had made a commitment that they would take care of my father if I entered the order.

But he was refused admission to St. Mary’s on Clayton Road. He was put back in the ambulance, and sent down to St. Mary’s Infirmary on Eighteenth Street. So you see, that was when I made a commitment to myself and to my God and to my parents, I would never, ever let anybody forget who I am, and whose I am. I don’t mean God’s creature. God allowed me to have a heritage which is African. So when I pray with other people, I will remind them even in Madison, Wisconsin, where I was a few weeks ago, I was asked to give a closing blessing for the dedication of the new wing, I closed with telling them, “And in my Black church, we usually say, ‘Let the church say, Amen! and that’s what I’d like to do.’”And the whole place said, “Amen!” But they had to identify where I was coming from. And I never, ever, will let anyone else forget me or mine. That was my father. He died three weeks later at St. Mary’s Infirmary for the Colored. Think about that one. What would you have done?

On Firmin Desloges and Homer B. Phillips Hospitals

Father [Alphonse] Schwitalla used the scripture from John, that says, I am the vine, you are the branches. And he used it to justify having St. Mary’s Infirmary for the Colored as the branch. The vine was on 6400 Clayton Road. And when I saw his picture in [St. Louis Magazine] I thought, oh, Lord, do I tell her about this?

In 1933, he built what was called Firmin Desloges Hospital. It’s now called Saint Louis University Hospital. The Firmin Desloges Family gave a million dollars to the Jesuits to build a hospital for their medical school. Father Schwitalla and our Mother Concordia were very dear friends. When he built that hospital — and I’ve never seen it in writing, but I do know there was a racist system in 1933 that was still in existence, and when the hospital was completed, we became the administrators, the Sisters of St. Mary. Most people thought we owned that hospital. We didn’t own that hospital; we were the administrators, for the Jesuits, of that hospital.

Mother Concordia, hand in glove with Father Schwitalla, actually helped to found the Catholic Health Association in the United States. And, you see that book there, Pioneer Healers? it’s right next to Roots on the second shelf? Okay, there’s an article in there. Sister Hilda and I are both special items in that book. Just simply because Black women religious, most of them are involved in education. For our order to have received Black women, maybe, maybe, at any rate, that’s what that book is about. It’s about how Mother Concordia and Father Schwitalla and all those people founded the Catholic Health Association, and out of that grew all of these others, and they have different sections for different women religious and what was going on in those days of, it was supposed to be physical healing, but they were not looking for reconciliation or to fight racism. Everybody just sort of rolled over and let it happen, and let it be.

It was two sisters who wrote that book, when they finished, they added that the book would not be complete without acknowledging Hilda and myself. Hilda became an X-ray tech, and actually as the years developed, before her death she was also on the faculty of Saint Louis University, in the school for radiological technicians. And for myself, eventually, see I’m starting my senior year in nursing school and when I entered the convent at St. Mary’s Infirmary for the Colored, and there were friends of mine who wrote and said, “What you doing in that Jim Crow novitiate? Why are you there?” Well, see, for me it was a bigger item. We were considered at St. Mary’s Infirmary, it was like sending us to Africa… the trade professionals went to St. Mary’s Infirmary.

At the same time, they were building Homer G. Phillips Hospital. The gap is, nobody gives credit to the sisters for what was happening at that time. The Black physician had no place to take his patients. The Saint Louis University opened up Firmin Desloges Hospital — for whites only. And someone has said that the Desloges family had stipulated that, it would be whites only. That’s why I say that I haven’t seen it in writing, but whether they did or not, it was de facto for whites only. We could go to the clinic. If we needed hospitalization, we had already in the master plan re-opened St. Mary’s Infirmary in 1933, when Firmin Desloges opened, St. Mary’s Infirmary re-opened, and the Black physicians working with Saint Louis University doctors, they actually formed their own medical staff, at St. Mary’s Infirmary for the Colored. So anybody of color that got sick and needed hospitalization, if you showed up at the door, well, I’m sorry, but we don’t take colored here, that hospital is down on Papin Street and Eighteenth.

At the same time, Homer G. Phillips, the lawyer who later was murdered, I don’t think he ever saw that hospital completed. He did the main thrust to get Homer G. Phillips Hospital going. And because of his interrelationships in the community, and they were not good, because he was fighting racism, and he was an attorney, he was killed on the streets of St. Louis. I don’t know, the book doesn’t say that part of it. Those are the gaps. So while they’re building Homer G. Phillips, the Black physician, strategy-wise, had prepared themselves as a medical staff at St. Mary’s Infirmary, because Homer G. Phillips didn’t open up until late ’36 or ’37. We primed them to be ready when Homer G. Phillips was finally opened. Those doctors had experience, not only together as a team, but they were also were instrumental on being on the very ground floor of forming the medical staff for Homer G. Phillips. And that place gained an international reputation in the medical world, because of the way that it was structured. The original strategy, nobody mentions it. I have a book that someone gave me for Christmas or for my Diamond Jubilee, and they talk about Homer G. Phillips, but they never mention that three or four years in which the sisters actually… it’s the flip side of a coin.

On friendships in the order

I was baptized Catholic, conditionally baptized, in ’42. This was three and a half years later, it was 1946 when I entered, July the 26. I didn’t know that just wasn’t the way it was supposed to be [laughs.] I mean, you know, I was too new in the faith to really know, well, this doesn’t really look quite right. But other people were writing to me, and my thought was, if this was the way that St. Louis was going to be, for every and ever, because the Catholic church through its hierarchy was approving it, and Rome had approved it, who was I to question? But my thought was — you know how uppity young people are — anything they can do, I can do better? And these are my people. So, if I’m going to become a sister, and care for the sick and the poor, and the poorest of the poor is us, I want to be where it is needed. And so based on that, and finding out that at least the sisters were going to take Black women in the order, what they heck? I’ll go for it! You know, because I will be there where my own people are. And if they’re going to get care, they’re going to get the best of care, because I got it [laughs].

Hilda came from Brooklyn, N.Y., and when she came from Brooklyn, she was a high school kid. But she had heard several years before that, that they were going to take African American women. And so she came, and finished high school at St. Joseph High School, which was designated by the Archbishop as for the colored. Sisters of St. Joseph had that high school, and they gave their very best to that school; it’s in Carondelet, St. Joseph. That high school. And so Hilda finished high school there, and then lived in the attic of St. Mary’s Infirmary, which was shown in the documentary.

She lived in the attic of that hospital until July 26, 1946. She had finished, I don’t know if it was a whole year before, but while she was finishing high school, and while they were preparing the old convent, we as student nurses, lived in the old convent in dormitories… if you were facing the building, just to the right is what we call the new nursing home, well you know that’s sixty-some years old now. (Laughs.) But it’s a younger building. So we moved over there in March.

I was one of the first ones to move over there in March, and at the same time, they were refurbishing the old dormitories and making them into the novitiate, the house of formation for us, for anybody that came that wanted to enter the order that was of color, they entered through that avenue, because that was how racist St. Louis was at that time.

On stories

I try to be open and candid with people. And whether they agree with me or not is not the point. It’s planting a seed that they can deal with long after I’m gone, so they’re still thinking, “Where does that fit in this beautiful tapestry that God has allowed me to become?” Anybody who wants me to talk, I think, oh, I don’t want to tell this story again. But it needs to be told. And each of us has a part of that story. It’s what we call “my piece of the truth.” I don’t have the whole thing. But I have a piece of that pattern, that’s mine. And if I put my piece with your piece, then we will have P-E-A-C-E. And we don’t have that now, because we don’t have those pieces together and we really, if it gets to close and it starts getting on stuff… “Well, I don’t know if I want to do this or not.”

I went back to Bloomington, and one of my nurse friends that had graduated from St. Joseph, we went to eat in a restaurant there, and they brought a plate out for her with her hamburger and brought a plate out for me. And she said, “Well, what is this about?” I didn’t have to ask the question. But at the same time, they’re saying, we don’t serve coloreds here. And she said, “Well, I think you will.” So she gave me the plate. We both had hamburgers. I probably had more onions on mine than she did [laughs]. But she took the plate, and put it over for me, and they gave her a milkshake in one of those metal things, and then you pour it into your glass. She passed the glass over to me, and she took the metal, and put the straw down in the metal container, and we sat there and ate. I know what she was thinking: “Now, you let them call the police on me.” [Laughs.] But you know what I was thinking: “Lord, don’t let them call the police on me!”

On the Black Sisters Conference

Our Black Sisters Conference was what I was talking to you about in one phase. That’s when I was here in St. Louis, attending Saint Louis University, learning how to administrate a hospital, which I was already doing! (Laughs.) I was coming down to St. Louis every summer. The Catholic Health Association, with Saint Louis University, they had this program going, so I came down for crash programs for three summers, and so then that’s one of the Jesuits approached me at a meeting and said — Hilda was still alive — he asked if either one of us were going to the gathering of Black Sisters, the Caucus of Black Sisters. And I said, I didn’t even know anything about it, because I was sitting up in white Baraboo. And that kind of news was definitely not in the Clarion-Ledger (laughs). But, anyway, he told me about the Sister that he knew that knew something about it, and I knew her, too.

So I wrote to her in Chicago, and she sent me a copy of the information from the National Catholic Reporter, at the time they carried the information in the letter. And so then I got on the phone and called for the General Superior, because she should have had a letter, but I didn’t get her, so I sent — because email had not come in (laughs) — a snail mail copy of the letter, and said if you have not already appointed somebody to attend this, then I volunteer.

So I went hiking out there, but when I registered, because of my position, by that time I’m the administrator of this hospital, and no Black sister is doing anything like that. So I was invited to speak on being the Black sister in the predominantly white community. And that meant predominantly white religious order, and predominantly white community of Baraboo, Wisconsin, where in 1933 some of the white people up there, some of the volunteers up there told me that they’d had a lynching.

When I got there, I was invited, and I prepared my paper, and I got there and the very first night of the open conference, in the sister’s auditorium, well there were some white folks, including the press was there — I mean, three or four hundred Black sisters? Nobody had see… I mean, I hadn’t seen that many Black sisters myself! So it was really like a family reunion, where we didn’t even know we had relatives there, that kind of thing.

The very first night, they had this Black preacher speaking and the first thing he did was to invite anybody who did not identify as being Black… they were asked to please leave the room. (Gasps.) I was horrified. I was horrified, because us, doing the same thing to them that they did to us! And I don’t want to be in that category of people. Well, then the more I heard, the worse it got. But really, actually, the program was set up wisely. We had young folks, old folks, Catholics, ex-Catholics, divorced Catholics, every walk of life, doctors, nurses, you name it — psychiatrists, psychologists, all Black, all talking about our family business. I began to get it. That this is family business.

Truth be told, I knew my paper wasn’t Black enough… I didn’t use the word Black anyplace in my paper. I was still a “negro.” Which was a given name by white folks. And when Stokely’s breaking out, and naming us Black and beautiful, that’s a name that we, being self-determined, had decided on. Well, then later on we also went to move from Black to African American. And then there are those who say I’m of African heritage, but I’m not American, I’m Haitian, or I’m Jamaican-American, but I’m in this country now. So name-calling is really a big part of this.

But I decided my paper wasn’t Black enough. Everybody else was doing this family reuinion, “Girl, did you know…” So, they’re from New Orleans, and this one is from Africa — there were people there from Africa, Black sisters were there that happened to be studying in the country, and we invited them to come into our gathering so that they were a part of it. And we had glorified Africans.

So I started re-writing my paper. That night, I was re-writing. I did the handwriting, because I thought that if I mess this up, I’m going to have to reconstitute it, so I’ll handwrite this, and where I have a different part I’ll footnote it or something. Girl, it got down to Wednesday night, and I knew it wasn’t Black enough. And I knew that I wasn’t Black enough, cause there were some people there — even though Father [Maurice] Ouellet says that I was as Black as Black could be, I thought he hadn’t seen any Black folks (laughs). And even when when I’m anemic, the man is saying that (laughs.) I decided, well, I got to let this stand.

Well, I got into the middle of my own corrections, and blackening my paper, and I ran into a quote in my own paper, from John 23: “The truth enobles the person who speaks it, without regard for human respect.” And I was sitting there, with my own paper, with that quote in my own paper, and trying to rewrite it. I was doing the very thing that brings one down from being ennobled. Because if I spoke the truth, it was my story, if Black folks and white folks helped me to get where I was, what right did I have to denigrate a white person and drag them down? Uh-uh.

But human respect was saying, water that down, or don’t use that sentence for heaven’s sakes. I thought, well, I’m going to leave my paper the way it is. It’s right there, and it was like God was speaking out of the paper, what are you doing? I still wasn’t convinced. So I decided, I’ll wear my gray suit tomorrow. I put on my little gray cotton suit, cause it’s summer, it’s August. And I had on a white blouse and my little gray suit. And the speaker that spoke before me that Thursday morning, he said, “Now lemme tell ya, ain’t no room in this movement for gray people!” (Laughs.) That’s exactly what he said! Oh no! (Laughs.)

So I took the jacket off, cause I was the one to get up, I was the next speaker. And I thought, I am just going to speak from my heart. I got up there, and I said, “You know what, y’all, because I had been introduced as the administrator of a hospital, and this is family business…I’ve become convinced that this really is family business. And I have heard so much Blackness, and Black being spoken of all over the place, to the point to which I have to admit that I’ve been intimidated. And my guess is that I’m not the only one here who’s in that condition. And my other guess is that I’m much older than most of you.”

The other sisters from those predominantly Black communities, they were older than I, they were well past their 40s. I was still in my 40s. Most of the people in that picture were in their late teens and early 20s. And I mean, these are young people! And here I am, addressing these people and the word is Black is beautiful. And the word I grew up on for years was Black is ugly, is mean, is nasty, is dirty. Black is not good. Black is bad! And I said to them, I even tried to rewrite my paper. But I have come to the conclusion that this is my story. And Black folks and white folks have helped me to get where I am, with the help of God’s grace. I am who I am; and I cannot deny my Blackness, but I cannot deny that there are some people out there who are not Black, but they have compassion, they have concerns… I cannot tell my story and then start weeding out parts that say something good about somebody else. So, I am going to give my paper as I have written it. And I just stuck to the paper.

Several different times, I got standing ovations during the talk. And then there were sisters who came to me afterwards. And they were in that category, they were intimidated. Here’s how they approached me: “Antona… uh, uh, I sure am glad you said what you said…” And they’re watching — they’re making sure that the other people don’t see them shaking hands with me, because those were the other people who strongly Black is beautiful and anything other than that is ugly. And so they’re holding my hand, but they’re looking to make sure that they shook it at the right time, they know that those other people are not looking. They were intimidated. And I said, well, I had make my own decision, and do what the Spirit told me to do.

On listening to Spirit

And by that time, they had this song, most of the time when I do speaking, before Black folks, white folks, all kinds of folks, young folks old folks… (singing) “I’m gonna say what the Spirit says say. I’m gonna say what the Spirit says say. And what the Spirit says say, I’m gonna say, Oh, Lord, I’m going to say what the Spirit says say.”

And then I say, y’all heard it. And I know you must’ve heard that melody sometime before. But just join me in saying (singing): “We’re gonna do what the Spirit says do. We’re gonna do what the Spirit says do. And what the Spirit says do, we’re gonna do, Oh Lord, we’re gonna do what the Spirit says do.”

I’m quoted across this country by black priests giving their sermons, “Like Miss Ebo says in St. Louis, we got to do what the Spirit says do!” And I use it even, I talked to a little parish, a mission, but we call it revival in the Black church, but it was a mission weekend or something. It’s three nights, and I preached it. They invited me to come and preach this. So, I did. But each time I began with that song, and by the time I left, everybody knew that song. And then they had a little reception on the last night, and I was over eating crumpets and drinking punch, it was probably diet punch, and I hate anything diet, but I was trying to put up with it, but I was trying put up with this stuff and act like I was socialized and civilized (laughs.)

The kids were over in the far corner, in the same room, or auditorium or reception hall or whatever, and a couple of the kids came over and said, “Sister Ebo, Sister Ebo… we want you to come over there with us and sing that song one more time.” I said, “You’ve got to be kidding!” And they said, “No, we don’t want to forget it.” And I said, “I don’t want you to forget it,” so I said, “Bye y’all,” and I said goodbye to the adults and went over with the kids and had a heyday with those children. We were singing, “We’re going to do what the Spirit says do…” And those children had it, just like that. But they wanted to make sure they had it right, so that when I was gone, they’d have it.

I’ve had people call me on the telephone and say, sing that song for me. One woman said she was standing in the kitchen and she was stirring the soup getting ready for the evening meal and she found herself (hums.) And she was thinking, where’d I get that song? Oh, that’s Sister Ebo’s song! (Laughing.) And that’s prayer, and that’s making a commitment: I have faith in the Holy Spirit. And Jesus said, I will send my Spirit to be with you. I will not leave you orphans — my Spirit will be with you. So I have faith in the Spirit. (Singing.) “I’m gonna say what the Spirit says say; I’m gonna say what the Spirit says say. And what the Spirit says say, I’m gonna say, Oh, Lord, I’m gonna say what the Spirit says say.”

Have mercy! And that’s another one of those coined expressions. People talk to me now, and say, “Well, you haven’t said, ‘Have mercy’ yet!” (Laughing.)

Beautiful!