Let’s have a moment of silence for all the sourdough starters that didn’t survive the pandemic: Jane Dough, Simon and Steve, Vol-dough-mort, Arctic Hilppa, and Anonymous, a Mayflower descendant.

Others — like Clarice — went professional. (Ms. C, as I discovered, is now a minor celebrity.) Most Americans burned out on keeping a kitchen ingredient that doubled as high-maintenance pet. Some didn’t wait for their yeast to starve to death; they just washed it down the drain.

Now most of us don’t even cook dinner at home, and are back at our prepandemic takeout ways. Our ancestors might sigh a sad sigh, especially the grandmothers and great-grandmothers who seasicked their way across the ocean with generations-old sourdough starter tied into a cloth. Perhaps we should also feel a stab of shame re: our late sourdough starters when thinking of Veena Mehra, who sneaked an heirloom yogurt starter in her purse before flying home from Mumbai, and has now passed it down to her granddaughters.

But there’s a similar washout every time America gets a wild hair to be more sustainable or go back to the land. That impulse is fueled, like lockdown baking, by crises. World War I radicalized Scott Nearing, who, with his wife, Helen, wrote one of the most influential homesteading texts ever, Living the Good Life. The young people who lived through the Cuban Missile Crisis, multiple political assassinations and the Vietnam War dropped out and literally headed for the hills. The 2008 financial collapse and hysteria around “peak oil” fueled a mini homesteading rush. Despite all those long-gone sourdoug starters (RIP!), this summer’s freak weather and $7 loaves of bread are creating another round of jitters and a hankering for a simple, earthy life of self-sufficiency.

Historian and urbanist Jane Jacobs, in conversation with Whole Earth Catalog’s Stewart Brand (another back-to-the land celeb), pointed out that this has been happening since cities existed. After the fall of Rome, urban people headed back into the countryside in search of the bucolic life. And so it goes, over and over.

From the first to the fourth wave

The reigning stereotype of the back-to-the-lander is still the Whole Earth Catalog hippie: an androgynous raggamuffin in earth shoes and a grubby paisley shirt. A person with sprouting jars in the kitchen window. A person who grows potatoes in a pile of dirt behind the shed and uses freshly plucked twig in lieu of a toothbrush. But those hippies stood on the shoulders of the generations before them, for better or worse.

As historian Jonathan Bowlder writes:

This countercultural quest for the good life outside of cities and away from mainstream society was rooted in the radical politics of the 1960s as well as in a much larger back-to-the- land tradition dating back to the 1890s…Often spurred by economic and political turmoil, Americans have turned again and again to rural space and the natural world over the course of the twentieth century. In going back to the land, many hoped to counter modern American society's trajectory by offering alternatives that were at times reformative and radical. These earlier generations wrote influential books and formed organizations, many of which influenced the third generation in the 1960s. Indeed, some older practitioners were still alive in the 1960s and 1970s and directly interacted with and fostered the younger generation’s pursuit of the back-to-the-land endeavor.

While documenting those earlier movements, Bowlder discovered a little-discussed aspect of homesteading in the U.S., particularly with “second wavers” like Ralph Borsodi and Scott Nearing, who embraced the eugenics movement. Though the hippies rejected eugenics, Bowlder points out that they still struggled with racism in a different form, valorizing Black and Native activists while segregating themselves and “turning inward towards a New Age identity that forestalled meaningful interactions with Native groups and Native causes,” as well as embracing “an enduring impulse amongst white, middle-class Americans to reject urban space as a response to contemporary socio-political — and by the late twentieth century environmental — upheavals.”

Bowlder says a lot of fourth wave homesteaders, including his cousins, decided to stay near their parents’ farms and start their own homesteads, but that they can’t be pegged so easily in terms of their politics. They are not a monolith. Some lean far left, some lean far right. Some have a libertarian streak. Some just want to raise cows and babies and post cute pics to Instagram. You can see all of these threads if you scroll through the Instagram feed of The New Pioneer, the Millenial answer to Mother Earth News.

Back to the (paved, smoggy) land

While well-to-do hippies bought farm plots in Vermont, Tennessee, Arkansas and California, there was a smaller, less visible movement happening: urban homesteading. Sometimes staying in the city was a necessity. Sometimes it was idealism. Sometimes it was both.

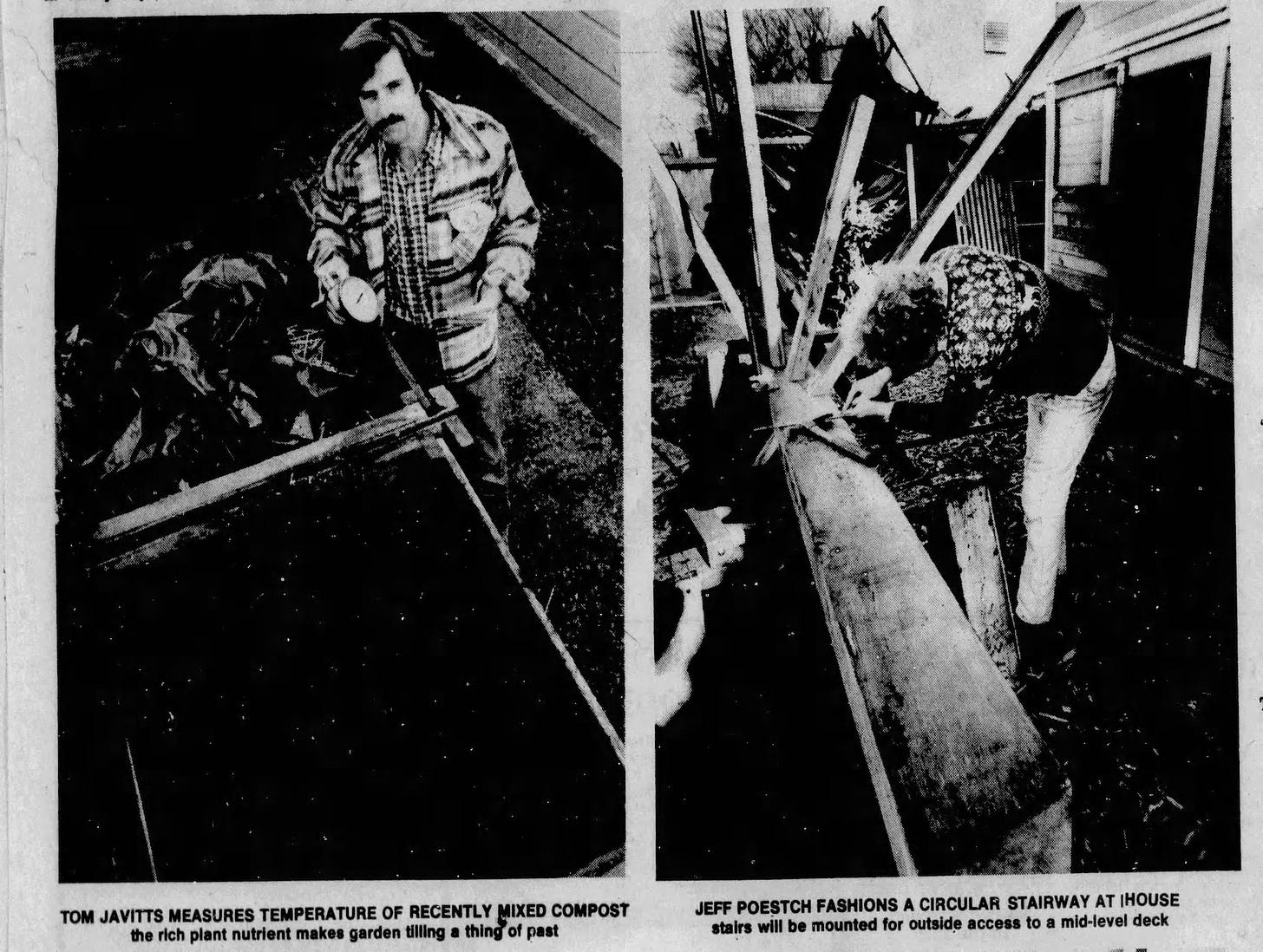

One of the best-known urban homesteads was the Bay Area’s Integral Urban House. As Mother Earth News perkily reported in 1976:

Away out here in Berkeley, California — in an aging semi-industrial neighborhood — an enthusiastic group of "doers" has come together to restore (and display to the public) a 100-year-old Victorian house. What's so unusual about that? Nothing . . . except that the stately dwelling—now known as the Integral Urban House—has become one of the country's most innovative and successful "urban homesteads." Half a dozen IUH residents grow their own fruits and vegetables, raise chickens, rabbits, and fish, recycle 90% of their wastes, solar heat their hot water, and conduct a variety of alternative technology experiments . . . all on a 1/8-acre city lot!

The collective behind IUH, the Farallones Institute, published a fat handbook of the same name with blueprints and instructions on how to transform your domicile into a closed system.

I probably don’t have to tell you that most of the people who bought the book just stuck it on a shelf and forgot about it. Perhaps they talked themselves out of the trouble after tuning into PBS to watch British sitcom Good Neighbours, which follows the misadventures of Tom and Barbara Good, a London couple attempting to live off-grid in their flat, who mostly just succeed in annoying their posh neighbors.

Countering the countercultural narrative

The other homesteader that caught the nation’s attention in the ‘70s was a teenager writing under the pen name Dolly Freed. Her book, Possum Living, released in 1978, detailed how she and her dad, who she calls “the Old Fool,” lived 40 miles out of Philly on less than $2,000 a year. After Frank Freed (his official pseudonym) saw young girls up to their elbows in toxic chemicals in a factory, he quit and eschewed the nine-to-five life. Instead, he and Dolly found ways to live on as little money as possible: they foraged, fished, cooked, kept rabbits and chickens, scavenged roadkill and brewed dandelion wine and moonshine.

In April of 1979 — when she was 19 years old — Freed met up with Chicago Tribune writer Jim Quinn in an expensive Philadelphia restaurant. As Quinn noted, the tab totalled a third of what the Freeds had spent on food the entire year prior.

Dolly “dressed in thrift store clothing that cost a total of $2.69 — a black cape from the 20s with ornamental embroidery, a beret she found in a trash can with a bright old-fashioned pin of real pastework,” Quinn wrote. She was “at least as well-dressed as any woman in the room, quietly delighted, with the good looks of plain country health (she runs five miles a day), and away of slipping in and out of sophistication that makes her seem sometimes two years younger and sometimes five years older than her age.”

When he asked her about eating squirrel, she schooled him: they “don't have enough meat to bother with,” she told him. “Pigeon is really delicious and in a city they'll come right up to your hands if you just call. 'Curr, curr,' she goes softly and makes a quick motion with her hands that would probably break a neck.”

It was “silly,” she said, to join a rural commune. “The reason you have all that magnificent solitude when you homestead in the Maine woods and West Virginia mountains is that no one in their right minds can stand to live there,” she said. All the people she knew who’d decamped for the woods, she added, “come from pretty rich families — they buy chainsaws and power tools and expensive woodburning stoves, and they're just as much a part of the money economy as they are in the city.”

Around the same time that Possum Living came out, there was another urban homestead in Philadelphia going against the stereotypical grain: the radical Black vegan collective MOVE. Sadly, MOVE also garnered a lot of media coverage, for very tragic reasons; during a standoff with police, 11 members died and dozens of nearby blocks were burned to the ground after law enforcement dropped a bomb from a helicopter onto the roof of the house. (MOVE still exists, maintaining a collective house in Philly and an active website.)

Members of Twin Oaks (one of the farmsteads in Jonathan Bowlder’s study) note that in addition to MOVE, “there have always been BIPOC communities, like those formed by self-liberated black people in the Dismal Swamp and across the South before the Civil War, and Indigenous Nations across the country who carry on their ancestral traditions in spite of attempted cultural erasure. This legacy of resilience is continued by BIPOC who are creating their own intentional communities in the present day.”

This Guardian article reports that cities are teeming with small-scale farmers of color (who often have to fight hard to stay on their plots), as well as many small-scale growers like Chantal Johnson, Jaquelin Smith, Aja Yasir, and Leah Penniman of Soul Fire Farm who are making up the fourth wave of Black organic farms and homesteads.

Walden, too

In 2010, Tin House re-issued Possum Living, with an epilogue/update/mea culpa from Dolly. She now works for NASA, has a family, and doesn’t eat roadkill or brew moonshine. In 2003, the Nearings’ biographer, Greg Joly, discovered that just like Thoreau (whose existence was more comfortable than he let on) “the good life,” didn’t quite match what the couple committed to paper. In fact, he discovered they spent about four months a year living in their apartment in New York City. Helen Nearing, who had family money (Scott Nearing did, too) purchased a new truck every year.

“I’d heard that from natives up here, and thought it was sour grapes,” Joly told The Bangor Daily News. “But in Helen’s diary she lists the new trucks.” He was disillusioned with the Nearings, he said, “but I’m not disillusioned with homesteading.”

There are a lot of people who’ve found their stride with homesteading and living in low-impact ways. New Roots Urban Farm, in my old neighborhood in St. Louis, has been at it a good, long while. So has Mr. and Mrs. Homegrown of Root Simple. So has Jay Babcock of Landline. So has Anne-Marie Bonneau, aka the Zero Waste Chef. So has David Holgren, one of the originators of permaculture. He’s helping people retrofit their suburban houses, in an evolution of the 1970s urban homestead movement. So has Low-Tech Magazine, which now has a totally solar powered website.

In New Orleans, we worry about toxic marsh fires, the saltwater wedge in the Mississippi, undrinkable water, unnaturally hot summers paired with crazy Entergy bills, drought, dying palm trees, and of course, hurricanes. People here, especially those who lived through Katrina, keep food stores, water stores, and generators on hand. Just like last time, they know they’re probably going to have to save themselves.

Anyone reading this has their own list of worries peculiar to their place in the world. Which is why homesteading will never stop, even if the popularity waxes and wanes. Perhaps the important point of intersection is where our personal concerns about survival overlap with the well-being of everyone else, including humans, plants, animals, water and soil.

In the past, what’s failed is veering too far in either direction: holing up in the hills with hoarded supplies, or feeling holier-than-thou about the environment and losing steam when the idealism gets threadbare. Neither approach has any humor, play or joy in it. And that means eventually, when people come to their senses, they give up and do something easier.

The poet Gary Snyder once said the most radical thing you can do is stay home. That phrase irks, post-pandemic; we’ve just heard that imperative phrase too often over the past few years.

But staying home looks like so many things. It looks like 97-year-old botanist Margaret Bradshaw riding on horseback through the English countryside to document and save Britain’s wildflowers. It looks like food historian Sarah Lohman hunting down Amish deer tongue lettuce and the mulefoot hog. It looks like those obsessive people we know as birders. It looks like Grow Dat Youth Farm, and Open Source Ecology. And yeah, it can look like a mason jar on your countertop, home to a sourdough starter named Prue.

Homesteading and Housekeeping

Has it been a bit since Historiola! went out? Yes, it has, and I apologize for that. The end of the semester overfilled my brain cells while tanking my energy, but I have another post in the hopper to go up later this week. Then it’s back in the saddle, et cetera.

Some overdue thanks to go out: first, to Gena B., for the coffee! (Please check out Gena’s photography here. She’s an amazing artist.)

Welcome and thanks to new subscribers Val G., Erica T. , Roger J., Suhella I., Danny U., Charlotte P., Jeff N., E., and Sally B.

For those who have a few days off this week, have fun, however you choose to spend that time whether you opt out of holidays, order a Cajun Turkey from Popeye’s, do the cranberry sauce and football thing, or um, just bake some sourdough.

See you on the other side. Cheers!

The opening made me laugh until snot came out my nose. Thanks.

By coincidence your newsletter on homesteading as a through line in our history arrived on the heels of the death of another homesteader. Rosalyn Carter died in the small house in Plains, Ga. which she and Jimmy shared as home for 77 years, even when they were living in the White House. She still walked in the little garden everyday weather allowing. That garden they had kept together was still kept up. In her illness it was tended by the National Park Service in what she referred to as “her best perk ever.”